Natassa Pappa is a publisher with a background in graphic design and a passion for documenting the essence of place. After living and working in both Greece and The Netherlands, Natassa returned to Athens, where she founded Desired Landscapes, a small publishing house that blends print with urban exploration. Through pocket-sized magazines and walking tours, she brings cities to life, exploring typography, oral history, and the bonds between people and places. Her work has been featured internationally, and her latest venture, Desired Pocket, is a bookshop in the heart of Athens, uniting urban wanderers through reading, writing, and walking.

What inspired you to create Desired Landscapes? Can you explain the idea behind ‘reads to walk and walks to write’?

Desired Landscapes started from a personal urge to understand cities. It was mainly a vehicle for me to travel without traveling, and discuss urbanities with fascinating people from around the globe while experimenting with the means of documenting the urban experience. How do you write about cities? What kind of images communicate the sense of place without establishing clichés? How can a city guide become a tool and not an obstacle when you walk on unknown streets? All these questions summarize my research and are hosted in Desired Landscapes.

As for walking, I see it as a research method. I read about a place to own some context, and then I walk there to actually experience it, or I walk directly to reflect on the spot, and then write about it. It’s both academic and critical, as it is subjective, personal, and literary. Both are equally valid for my research.

How do you curate the content for Desired Landscapes to ensure it captures the unique visual culture of each city?

The choice of the authors’ voices is the core of making this magazine. But my aim with each issue, it’s not just to introduce stories of cities from unexpected angles, but to navigate through a set of fascinating urban qualities of iconic cities standing next to not-so-known ones – like in real life. That’s why each issue contains more than ten cities and is being edited for almost a year, to create invisible dialogues for the readers who care to read it as a whole. Then the image selection, which varies from snapshot photography to archival material (streetscapes, maps, designs, etc) creates a visual diversity in a dense pocket-size format, to hold and revisit for years to come.

Can you describe the feeling you get when you walk in a new city? Can you share some memorable experiences or insights gained from walking tours?

To me, walking in a new city can be equally thrilling, as it is overwhelming. I’ve written quite a few times about the angst that goes hand in hand with the excitement of exploring strange streets, for various reasons. Through the last decade, I’ve employed several methods to approach cities and tame such feelings, and this is what is shared in the city guide section of Desired Landscapes. This text offers entry points to cities, to allow you to feel safe, yet curious to find out more.

The walking tour format is a totally different story. In my case, it is the result of endless wanderings and urban research. A curated itinerary that takes away this angst and the fear of missing out when someone has limited time in a city and an experience that helps visitors form bonds with new to them cities.

What inspired you to create your first guidebook on the neglected Athenian passageways?

At first, it was more like an escape from 2012 post-crisis Athens, when cars, noise, trash, and chaos dominated its public space. The passageways – although sometimes dodgy back then – offered me access to a time capsule, where people really cared about the space around them. I would discover devoted family businesses with captivating vernacular shop windows, next to oral histories of a city that ceased to exist and was never documented. The proud feeling of these people building their life from scratch, independently, made me connect to Athens on a deeper level. The passageways are still the place I go to when Athens fails me. Their genuine nature and paradoxical presence inspire me and bring me hope.

How does Desired Pocket serve as a community space for urban wanderers? What experiences can visitors expect at Desired Pocket?

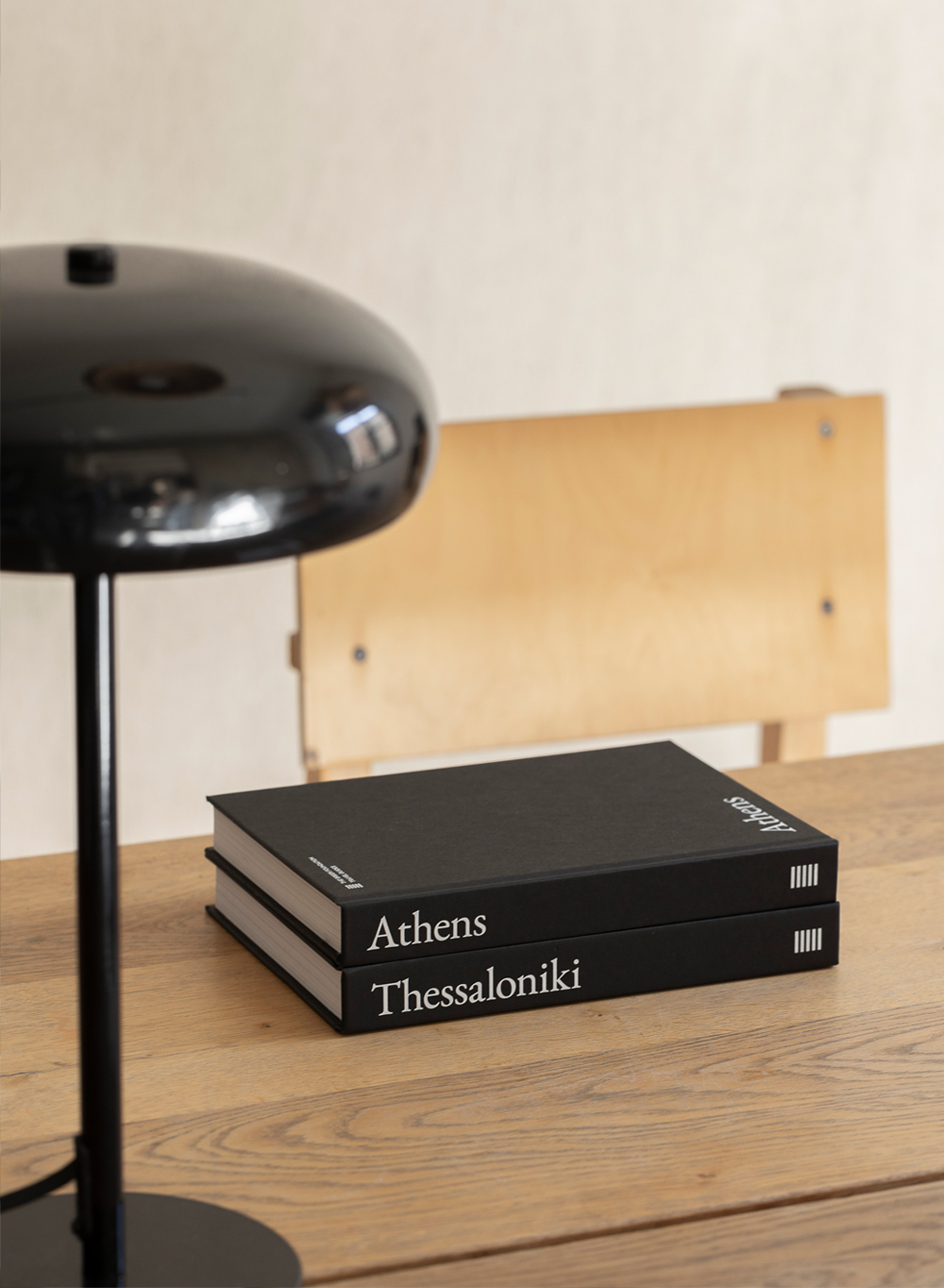

Desired Pocket was conceived as a space to offer a pause to avid wanderers. Located on the lower floor of Stoa Anatolis, next to banana trees and printshops, it forces visitors to slow down and connect to their surroundings. The shop’s tiny scale invites intimate encounters, while the featured collection of Desired publications sets a tone for urban dialogue. On a regular day, you will most probably find me there after a walking tour, 11–3 pm, to skim together through printed matter. Twice a month I’ll invite you to the Bibliography Sessions, or the Desired Writing Club at the roof, to meet like-minded people and discuss publishing and cities.

What are some of the most surprising or lesser-known aspects of Athens that you have discovered through your urban explorations? Can you share a particular historical fragment of Athens that you found especially fascinating and how it impacted your research?

Athens is a palimpsest, so what I’m always surprised to discover is the superimpositions of rather irrelevant elements. In such instances, time stops to be linear, and the city forces you to critically reflect on its past. It can be architectural details, lost crafts, or even public spaces that no longer seem to serve us.

Can you share some stories about the most interesting signs or typography you’ve documented?

“What fascinates me about signs is their ephemeral nature.”

There was a big, very well-placed exit sign in Stoa Tristrato. Pink plexiglass – as this used to be the main craft around the area – hung from the ceiling, until one day they renovated the building and had to put it down. It was then, that it turned into thousands of tiny pieces, as it was too old to bear any form of contact. A little further, in Stoa Kairi, the entrance sign bearing the stoa’s name, hides an older layer underneath, which with some close observation reveals more type forms, just upside-down. A form of recycling signs and accidentally preserving type history.

Are there any upcoming projects or new directions you are excited about?

Yes! Apart from the new issue coming this November, this February marks a decade of walking tours, so I’m preparing two pocket-books documenting the walks I’ve been doing.