An interview with Kalos&Klio about their work, the ongoing crisis, the media and the Kalos&Klio showroom.

Kalos&Klio (Christos Kalos, Klio Tantalidou), is an artist duo born in Thessaloniki, Greece, where they live and work. The pair has joined forces since 2005 and operates in a complementary fashion, considering the process of working as one, a path more intriguing. Klio studied painting at the Hanze University, Groningen, NL printmaking, at the Governors’ State University, Chicago IL, USA and holds an MFA in Digital art from the University of Chicago, Chicago, IL USA. Christos Kalos studied Photography at ESP school of Photography, Thessaloniki, Greece. The pair has participated in many solo and group exhibitions in Greece and abroad.

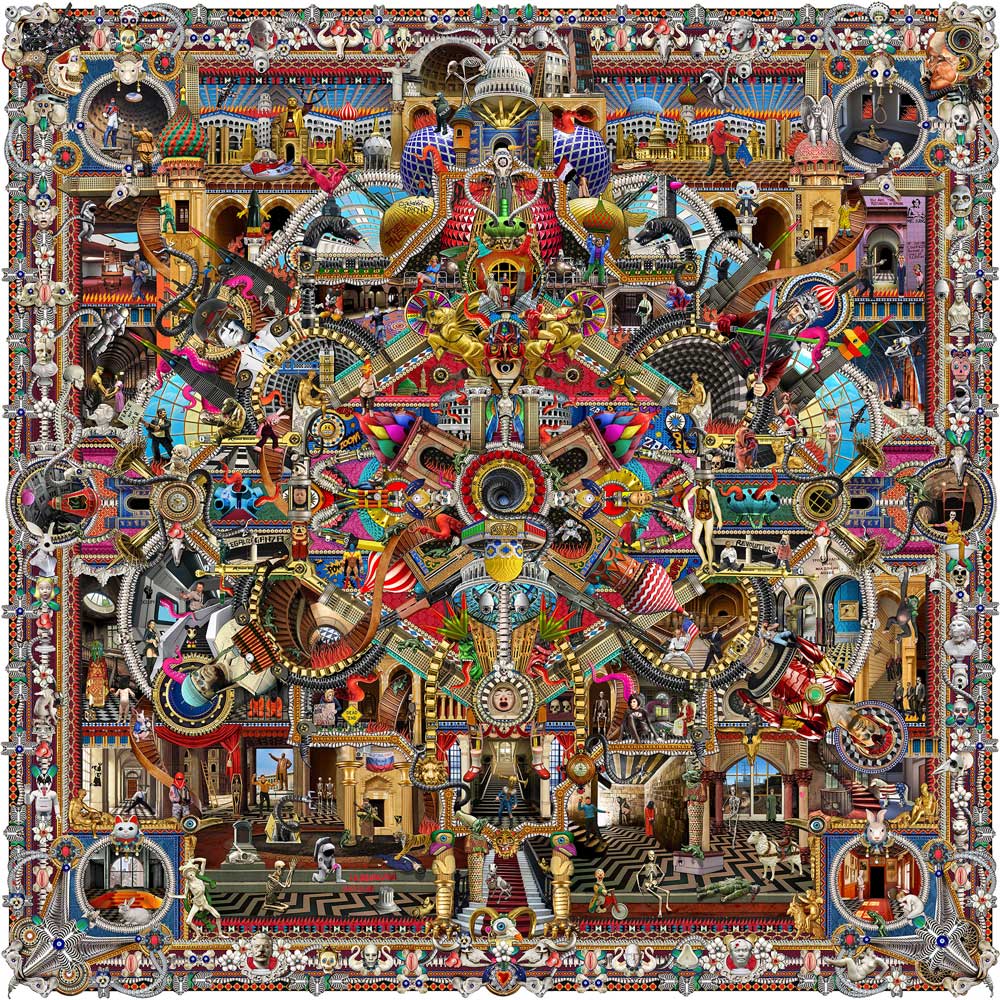

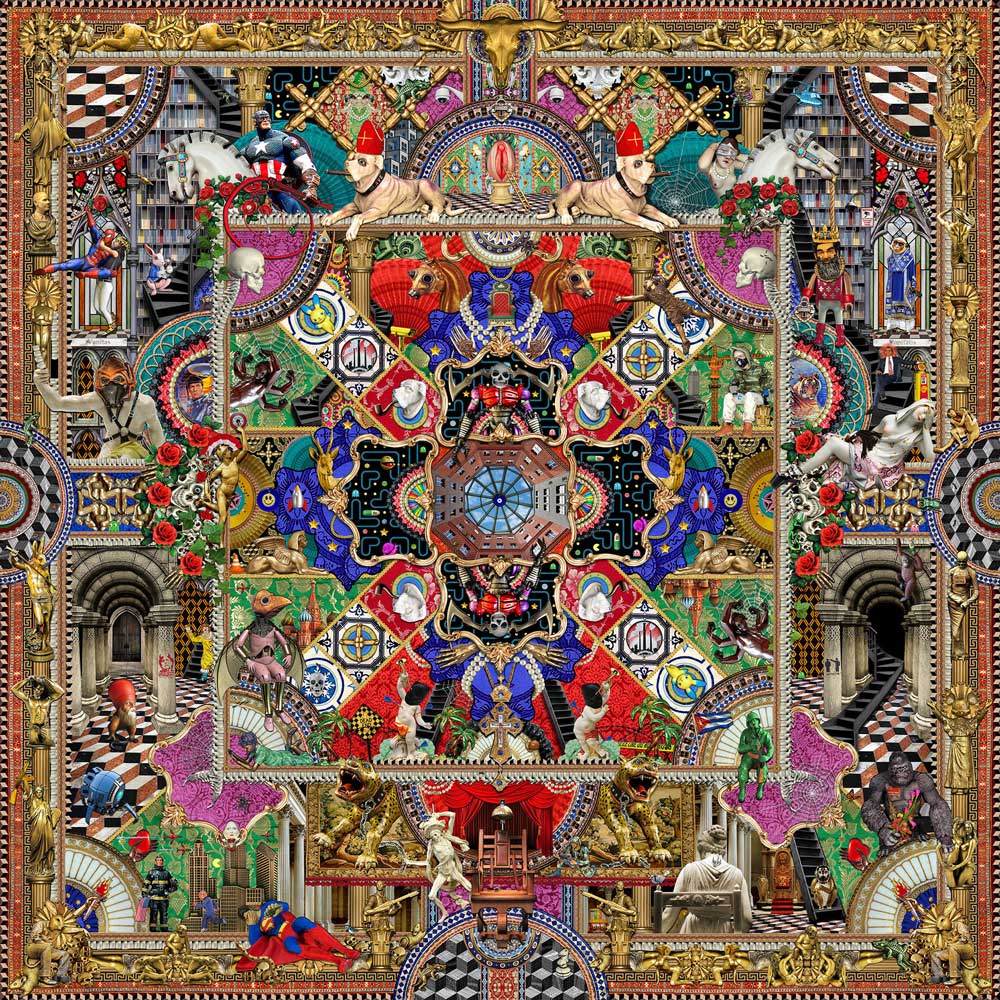

Your work has strong social references and connotations, such as for example ‘Violent Silk’, which deals with violence around the world. What aspects of reality do you aim at presenting to the viewer through your art?

We live in a world that appears to be more visible than ever, the perceiving abilities of the person-recipient are enhanced and access to everyday activities and human history through web search engines has become a reality, either as new windows to the world or as a kind of “panopticon”. A google search unveils bare views of the world, and to quote Jean Baudrillard “Since the world drifts into delirium, we must adopt a delirious point of view”. Our work explores this world; as digital nomads / archaeologists we seek for the traces left behind in the form of informational debris by the miscellaneous images (infojunk) that surface and sink in it. We retrieve and recompose its pieces from scratch, creating a global ‘mosaic’ of information, which brings together fragments of a panhuman material world along with elements of everyday life, in the way that we perceive it through the media, the internet, as well as through direct experiences that come from our wonders in the cities of the world.

These virtual / real journeys could not leave out violence as an element, which is the case e.g. in the ‘Violent Silk’ series, as violence is and has always been one of the fundamental components of the panhuman structure, from East to West, from ancient times to the present day. Our works are long narratives of the fragmented world that require filtering the digital and informational chaos using an attentive rather than a laid-back perspective. Using attractive form as a tool to approach the viewers, we invite them to explore the artwork, to reflect on it, to reevaluate the world surrounding us, to develop an interest in the connections we point out and to create new, different connections of their own. Besides, a work of art is always completed in the mind of the (contemplating and receptive) viewer. Our artworks do not call for superficial, passive viewers but fellow travellers that choose their own ‘reading’ paths, taking from each journey something with them, in the same way that we do.

In your work you use what you call ‘web debris’, i.e. images of the world lacking any actual essence. Do you think that the acquaintance of the wider public with images (through the internet, TV etc.) offers you larger flexibility in communicating your messages to the viewer, through the use of unconscious connotations and symbolisms?

Without any doubt, images have always been the primary means for disseminating ideas and for the public to grasp social reality. Of course, nowadays we are overwhelmed by a huge production of consumable images of every type, which rapidly alternate, attune and are assimilated before our eyes, creating a glut feeling and turning us consciously or unconsciously into addicted viewers and voracious consumers of virtual fragments. In a way, one can say that compared to the old days, people nowadays have been trained in looking at ‘fast food’ images, given no time at all to interpret their messages. As a result, most of them are uneducated in this regard and can rarely spend enough time looking at a work of art, unless it inflicts them no pain, concerns or disturbance, similarly to their inability to withstand a book that requires studying it rather than simply flipping through it.

We live in an era of a diffused viewing of everything and hence are subject to many art simulations e.g. objects lacking quality content that imitate works of art in the midst of a complete aestheticization of society, with consumable art pretending to be all around us. This is of course reinforced by the lack of actual education; image is a language itself and if one is accustomed to its codes, he can perceive multiple reading levels and thus grasp its content in a more substantial way. We believe that the difficulty in perceiving and receiving a work of art that at the same time deals with contemporary issues can partly be surpassed, and that’s why the visual language that we use in our work corresponds to our times, and embraces the public rather than fending it off, using as point of reference stimulus that are shared by the artist and the viewer. To put it short, we are interested in the world and not in “our world” as such.

Would you be interested in transferring the same logic of reusing depreciated objects in other forms of art or design?

Digital means and our times in general are defined by certain characteristics, such as fluidity, transformation and constantly pushing the limits. Nowadays, nothing is completely unbiased but instead things have been blended together, and each contains elements from different fields; our world is made up of hybrids. Besides, culture and art have always been the products of blending things together and have always been open to anything that can generate new ideas – and hence vital power – in order to evolve in a world that is constantly changing. The holistic approach of art to everyday life is something we have always found relevant and interesting.

Through your work you create real value out of ephemeral objects that lack meaning, a reverse process compared to that carried out by many media nowadays. Would you say that the ongoing crisis in Greece has led to a blatant degradation of the media’s modus operandi and that inevitably art becomes more and more important in informing and increasing the awareness of the public?

The mass media, or to put it another way, the Mass Media of Entertainment, in their effort to make fast, easy profit resort to anything that can attract and addict the public into more passive viewing, and are thus ‘bombing’ it with infojunk, i.e. a plethora of cheap and raw information overload. In the times of prosperity the media – without exception – dominated in disseminating products of visual and verbal pollution. Today’s crisis only added another main meal to their menu, comprising even more images of violence, stirred with other silly images as intervals. By gradually making this pollution the centerpiece of the spectacle offered to the masses, they refine it aesthetically, shifting the aim from sharing the actual essence of a piece of information to rather disseminating it as images that the masses are eventually unable to process and assimilate.

Amid this ‘pulp’ of informational garbage, the role of modern art becomes even more difficult, as it often tends to blend with the fusion of visual banality and sterile aesthetic pleasure. The end result is simulations in all forms of art i.e. things that appears to be art to the uneducated, but in reality are not! So we end up with a form of art that corresponds to the era of images but without actually conveying anything important; art that attracts viewers only for a few minutes; fast-food art. Hence, the difficulty that art faces today lies in the painful domination of its visibility. Nowadays everything is either described as art or invokes it, as for example advertising, which often uses the term ‘art’ to describe and add value to frivolous consumer products. We therefore believe that art can play an important role in modern society only if it manages to stand out from the visual garbage ‘pulp’ and refrain from being tedious.

In what way could art intervene in Greece’s urban environment, in order to move beyond the galleries’ narrow boundaries and become part of public space?

Prior to answering this ever-interesting question, we should note that Greece lacks even the basic urban environment (leaving aside the architectural quality of Greek cities) that could guarantee access to all citizens to public space, as the latter is trespassed and distinctively chaotic. To start with, the obvious would be for history of art and visual arts to be introduced in primary schools, in order for children to develop a genuine interest in contemporary Greek cultural production, which would translate to art being brought into public space as a natural consequence. In practice, open calls for tender addressed to private investors (the government could perhaps provide some tax incentives to private sponsors, albeit it seems to be moving right in the opposite direction) could be used to install more artwork in school buildings, squares, and public space in general. Art is truly vital in modern Greece, given the state of public space and urban environment.

Would you say that the crisis leads to more hard work and innovation or on the contrary, does it lead to a general depreciation, obsolescence and consequently a pursuit of cheap and superficial solutions?

The crisis has certainly brought things down from an economic perspective in the art and culture sectors, in addition to further aggravating people’s quality of life (and hence that of artists). Besides, art has always survived through sponsorships of all kinds and through the support of prosperous economic environments. The situation today seems more suffocating than ever, especially if one takes into account the increase in the number of artists and the simultaneous downfall of the art market. If we tried to look for something positive in all this, that would be the fact that these harsh conditions force people to either make it or to vanish, in a Darwin sense, similar for example to the many animal species that lived and were fed ashore but were forced to transmute in order to be able to swim and hence survive, as was pointed out by Darwin’s studies in the Galapagos islands.

What are the experiences you gained from running the Kalos&Klio showroom project space as far as collaborations are concerned? What initiatives do you think should be taken on behalf of cultural operators in order to promote a spirit of collaboration in Greece’s art sector?

Collaborations are fundamental in the way that we see the world – besides even Kalos&Klio are the result of a collaboration! What we’ve been doing at the K&K showroom since 2009 is building precisely on that spirit of collaboration, as we actively and constantly involve artists, intellectuals and creative people interested in the arts, both by organizing exhibitions but also through their participation in seminars, talks and activities that promote art and dialogue around it. As artists, we are definitely interested in collaborations and of course in cultivating a micro-ecosystem that can attract and stimulate both local and foreign artists. As for cultural operators, many of them – and particularly private initiatives – seek collaborations and cross-cultural connections, grasping the ongoing situation. Greece is not lacking ideas or cultural activities but meaningful synergies that can create the vision and essence that the former are usually missing.